This research guide is intended to encourage the researcher's candid evaluation and interrogation of the historical record. While UTRGV Special Collections & Archives is tasked with providing access to and preservation of our collections, our department does not approve, endorse, or support the attitudes, biases, language, or behaviors found among these materials.

Please do not hesitate to Contact Us if we can improve this research guide, including but not limited to language, description, addition or removal of resources, or access.

Historically, Black and African American communities in Rio Grande Valley have been small and tightly-knit (see McAllen Monitor, 1999). The first people of indigenous African descent arrived in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas as enslaved people. During the period before and directly following the U.S. Civil War, Black people also arrived in the Valley as freed men and women, establishing themselves as farmers and ranchers, including the Jackson, Webber, and Biddy families. Later, Black Americans would settle as members of the U.S. military, teachers, farmworkers, railroad workers, and other tradespeople—all seeking new opportunities in the Rio Grande Valley. This guide aims to highlight Black and African American communities in the RGV.

The first Black people arrived as enslaved Africans to the area that would become Texas, Mexico, and the United States.

Enslaved and free Black people came with Spanish exploring expeditions first as soldiers and later as settlers. They would become African Tejanos accounting for 15% of the non-native population of Spanish Texas by the end of the 18th century. Soon after Mexico won its independence from Spain (1823) and abolished slavery (1829), starting a wave of Black Americans migrating south and seeking freedom. However, Mexican Texas was granted exception and slavery continued well after Texas became its own Republic. Texas not only prohibited free Black people from coming to the republic, limited the emancipation of enslaved people, and restricted the rights of freedmen. (Barr, p. 7-11)

While the vast majority of Black and African American people arriving in Texas between the 1830s and the U.S. Civil War were also enslaved there is some emerging evidence that some families in the Rio Grande Valley helped people escape enslavement through the Underground Railroad in South Texas to Mexico. And, while President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation (1863) abolished slavery in the United States, Confederate States, including Texas, continued the institution until the end of the war. News of their freedom did not reach Black Texans until June 19, 1865, or Juneteenth, when federal troops arrived in Galveston to take control of the state.

However, the end of slavery did not result in the end of racial discrimination for African or Black Americans. The period following Reconstruction gave rise to increasing hostility as Jim Crow laws became institutionalized across the country including the military (e.g., conflicts at Fort Ringgold and Fort Brown). Black Texans were victimized by discrimination and segregation in all aspects of their public and private lives, and co-mingling with white people was generally forbidden and could result in brutal and even fatal punishment against black people. It was not until 100 years after emancipation that Black Americans were officially afforded the same legal rights as other Americans.

Juneteenth, or June 19th, is a federally recognized holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States. Although President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 to abolish slavery, Texas was the last Confederate state to emancipate enslaved people. In fact, freedom did not arrive for nearly two years on June 19, 1865 when federal troops assumed control of the state in Galveston and issued General Order No. 3 proclaiming independence for Black Texans. Opal Lee, a retired school teacher from Texas, campaigned for decades for the national recognition of Juneteenth. Her efforts were rewarded on June 17, 2021 when President Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law. Juneteenth has been celebrated locally since 1996.

Juneteenth: Freedom Day Library Resources: https://utrgv.libguides.com/blackhistorymonth/juneteenth

Collections include videos, photographs, programs, and other documentation relating to local Juneteenth Celebrations in the RGV.

Rev. John B. Norman (1896–1967) was born in Glen Flora, Texas. Soon after relocating to Edinburg, he founded one of its earliest African American churches, Lily of the Valley Baptist Church at the corner of 19th Ave. and Van Week just across the street from his house on Schunior Road. Rev. Segregation prohibited African American children from attending white schools. Therefore, Rev. Norman began teaching school inside the church and then in a one-room schoolhouse he built behind the church a few years later. The E.W. Norman School, named for the Edwards, West, and Norman families of Edinburg, served around 25 black school children during the 1930s. It provided curriculum for kindergarten through 8th grade, and early teachers at the Norman school included Rev. Norman, Verna Veil Butler, Ruby Leona Parker, and Melissa Dotson Betts. The E.W. Norman school closed in 1938 when the Edinburg Consolidated School District opened George Washington Carver Elementary School (on E. Lovett St.).

Melissa Dotson Betts (1902–1988) attended Wiley College (Marshall, TX) and earned her BA from Texas Southern University (Houston). Mrs. Betts began her teaching career in San Benito (1929–1934), but in 1935, she began teaching in Edinburg first at E. W. Norman School and later at George Washington Carver Elementary School (1014 E. Lovett). Mrs. Betts split her time between teaching during the week in Edinburg and spending time with her family in San Benito on the weekends. Like most teachers at so-called "colored schools", Mrs. Betts was the only teacher at Carver for multiple grades and was expected to fulfill the roles of principal, counselor, cook, custodian, and even the groundskeeper. She spent her final four years teaching at Austin Elementary before retiring in 1969. Thirty years later, Edinburg CISD honored her decades of service and education with the opening of Melissa Dotson Betts Elementary School (1999).

Parnethia Archer (1920–2003) was born in Cuero, Texas, and was a lifelong educator and resident of South Texas. She taught elementary school and special education for nearly 40 years and was herself a lifelong learner. She attended Booker T. Washington School (Harlingen) until 8th grade and returned to Cuero for high school. After attending Junior College, Miss Archer continued her education, earning a BA in education from Huston-Tillotson (Austin) and her first MEd from Texas Southern University (Houston) followed by her second from Texas A & I University (Kingsville). She taught for four years in Mission before moving to Weslaco in 1947. Miss Archer became the school teacher at Beatrice Allen Elementary School, which she campaigned to officially name. After integration, Miss Archer taught classes at Roosevelt, Sam Houston, and Stephen F. Austin before retiring in 1982 from Weslaco ISD and later All Faith Christian Academy in Harlingen.

Mittie Anita (Williams) Pullam (1913–2009) was most known for her historic achievement as the only African-American School Principal and the first African-American Teacher for the Brownsville ISD. Mrs. Pullam earned a Bachelor's Degree in Literary Arts from Samuel Houston College in Austin and a Master's Degree in Education from Texas Southern University. In 1947, she began teaching at the segregated school for African Americans in Brownsville, Frederick Douglass Elementary School (located on E. Fronton St.). Later in the 1960s, owing to Mrs. Pullam's high standards for curriculum, the school was incorporated into Skinner Elementary, where she continued teaching until her retirement in 1975—the same year she was recognized as the Elementary Teacher of the Year. Mrs. Pullam's devotion to students touched countless generations and inspired a grassroots campaign to name a school in her honor. Mittie Pullam Elementary School in Brownsville honors her three decades of service to her community.

Jean Marie “Joe” Callandret (1883–1931) and his wife, Fannie Sanco, moved from Louisiana to San Benito, Texas in 1908. Joe was a farmer and respected businessman, who was fluent in English and French. He and Fannie raised six children and were among twenty-four African American families living in San Benito in the 1920s. In 1921, San Benito became the first Texas school district to establish a one-room school for black children. However, the school fell into disrepair, was relocated several times, and was once destroyed by a hurricane. Seeking a more permanent structure for her community, Fannie donated land to the San Benito School District (1948). The new two-room cinderblock school house opened in 1952, and the Joe Callandret School served African American children from San Benito and Harlingen until integration in 1960. Today the former school serves as the Callendret Black History Museum.

The Rio Grande Valley Oral History Collection consists of over 500 digitized oral histories recorded and collected by faculty, staff, students, and community members and donated to the University Library. Oral histories provide unique, and in many instances, otherwise unavailable written information, and as such provide valuable insight into life in the region, including immigration, military service, ranching, education, agriculture, border violence, sports, and much more.

Photograph showing several headstones and crosses in the Restlawn Cemetery (part of Hillcrest Cemetery) in Edinburg, Texas. This property is designated as a Texas Historical Site and is believed to be the only graveyard in Hidalgo County designated for African American burials.

Photograph showing several headstones and crosses in the Restlawn Cemetery (part of Hillcrest Cemetery) in Edinburg, Texas. This property is designated as a Texas Historical Site and is believed to be the only graveyard in Hidalgo County designated for African American burials.

Learn more about Black Historical Sites in Edinburg, TX: https://www.edinburgarts.com/black-history-map

Historically recognized as the first church for African Americans in McAllen, Texas. The church served as a place of worship as well as the center for activities for the Black community. The church site is recognized as a Texas Historical Site, and the City of McAllen rededicated Bethel Garden to the community in 2019. Photo via hmdb.org, "The view of the Bethel Baptist Church Marker from the street." Photographer: James Hulse (Medina, TX), June 4, 2023.

Historically recognized as the first church for African Americans in McAllen, Texas. The church served as a place of worship as well as the center for activities for the Black community. The church site is recognized as a Texas Historical Site, and the City of McAllen rededicated Bethel Garden to the community in 2019. Photo via hmdb.org, "The view of the Bethel Baptist Church Marker from the street." Photographer: James Hulse (Medina, TX), June 4, 2023.

The Texas Historical Commission Marker Number 20105, reads as follows: "During the Civil War, African American soldiers of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) fought in the last battle of the war at Palmito Ranch on May 11, 1865. During reconstruction, Buffalo Soldiers were stationed at Fort Brown and many sites along the U.S.-Mexico border. In 1906, troops of the 25th Infantry Regiment, distinguished veterans of the Spanish-American War, were briefly stationed here. Conflict between soldiers and townspeople culminated in violence in August 1906. In the aftermath of the 'Brownsville Raid,' President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 men without a trial. The U.S. Army and President Richard Nixon reversed that decision in 1972 with mostly posthumous honorable discharges."

The Texas Historical Commission Marker Number 20105, reads as follows: "During the Civil War, African American soldiers of the United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) fought in the last battle of the war at Palmito Ranch on May 11, 1865. During reconstruction, Buffalo Soldiers were stationed at Fort Brown and many sites along the U.S.-Mexico border. In 1906, troops of the 25th Infantry Regiment, distinguished veterans of the Spanish-American War, were briefly stationed here. Conflict between soldiers and townspeople culminated in violence in August 1906. In the aftermath of the 'Brownsville Raid,' President Theodore Roosevelt dishonorably discharged 167 men without a trial. The U.S. Army and President Richard Nixon reversed that decision in 1972 with mostly posthumous honorable discharges."

Jackson Ranch was established by Nathaniel Jackson and Matilda Hicks, an interracial family, who moved to the area in 1857. The family ranch and cemeteries are recognized by the Texas Historical Commission. In 2024 the National Park Service added Jackson Ranch to its Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program.

Jackson Ranch was established by Nathaniel Jackson and Matilda Hicks, an interracial family, who moved to the area in 1857. The family ranch and cemeteries are recognized by the Texas Historical Commission. In 2024 the National Park Service added Jackson Ranch to its Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program.

Browse the Hidalgo County Historical Commission Collection for more information on the Jackson family: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/hidalgohist/

John Ferdinand Webber and Syliva Hector were an interracial family, who established the historic Webberville Community in Travis County Texas. In 1854, the family moved further south and purchased property along the borderlands of Hidalgo County, Texas, and Tamaulipas, Mexico. The “Webber Rancho Viejo” also operated a ferry to cross the Rio Grande River. It is believed the family assisted enslaved people fleeing south to Mexico.

John Ferdinand Webber and Syliva Hector were an interracial family, who established the historic Webberville Community in Travis County Texas. In 1854, the family moved further south and purchased property along the borderlands of Hidalgo County, Texas, and Tamaulipas, Mexico. The “Webber Rancho Viejo” also operated a ferry to cross the Rio Grande River. It is believed the family assisted enslaved people fleeing south to Mexico.

Learn more about the ranch and the Webber family via CHAPS: https://www.utrgv.edu/civilwar-trail/civil-war-trail/hidalgo-county/webber-ranch/index.htm

During the US Civil War, Fort Ringgold was occupied by the Confederate Army under Rip Ford and briefly recaptured by the Union Army from 1863-1864. It is recognized by the Texas Historical Commission but the historical marker makes no mention of the U.S. Colored Troops who served there during the period of reconstruction. Previous and yet similar to the Brownsville Affair, racial tensions between the Buffalo Soldiers of Troop D, U.S. Army Ninth Cavalry, and the civilian population escalated quickly following the October 16, 1899 shooting of two black soldiers after a gambling dispute.

During the US Civil War, Fort Ringgold was occupied by the Confederate Army under Rip Ford and briefly recaptured by the Union Army from 1863-1864. It is recognized by the Texas Historical Commission but the historical marker makes no mention of the U.S. Colored Troops who served there during the period of reconstruction. Previous and yet similar to the Brownsville Affair, racial tensions between the Buffalo Soldiers of Troop D, U.S. Army Ninth Cavalry, and the civilian population escalated quickly following the October 16, 1899 shooting of two black soldiers after a gambling dispute.

Before the Mayflower : a history of the Negro in America, 1619-1964

by

Traces black history from its origins in western Africa, through the transatlantic journey and slavery, the Reconstruction period, the Jim Crow era, and the civil rights movement.

Before the Mayflower : a history of the Negro in America, 1619-1964

by

Traces black history from its origins in western Africa, through the transatlantic journey and slavery, the Reconstruction period, the Jim Crow era, and the civil rights movement.

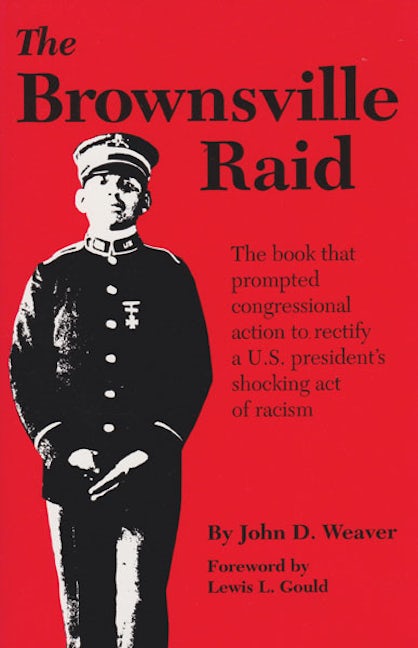

The Brownsville Raid

by

"Around midnight on August 13, 1906, shots rang out on the road between Brownsville, Texas, and Fort Brown, the old army garrison. Ten minutes later a young civilian lay dead, and angry residents swarmed the streets, convinced their homes had been terrorized by newly arrived soldiers. Inside Fort Brown, the alarm was sounded. Soldiers leaped from their bunks and grabbed their rifles, thinking they were under attack by hostile townspeople. The soldiers were black; the civilians were white. Still proclaiming their innocence, 167 black infantrymen of the segregated Twenty-fifth Infantry Regiment were summarily dismissed without honor (or a trial) by President Theodore Roosevelt. "The ""Brownsville"" Raid, " first published in 1970, is John D. Weaver's searching study of the flimsy evidence presented in a 1909-1910 court of inquiry. That court had upheld the president's action and closed the case against the soldiers, not one of whom had ever been found guilty of wrongdoing. The case remained closed until 1971 when, after reading "The Brownsville Raid, " Congressman Augustus F. Hawkins of Los Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department rectify the injustice. Amid a flurry of national publicity, honorable discharges were finally granted in 1972. All were posthumous except for that of Private Dorsie Willis, who received his in a moving ceremony on his eighty-seventh birthday."

The Brownsville Raid

by

"Around midnight on August 13, 1906, shots rang out on the road between Brownsville, Texas, and Fort Brown, the old army garrison. Ten minutes later a young civilian lay dead, and angry residents swarmed the streets, convinced their homes had been terrorized by newly arrived soldiers. Inside Fort Brown, the alarm was sounded. Soldiers leaped from their bunks and grabbed their rifles, thinking they were under attack by hostile townspeople. The soldiers were black; the civilians were white. Still proclaiming their innocence, 167 black infantrymen of the segregated Twenty-fifth Infantry Regiment were summarily dismissed without honor (or a trial) by President Theodore Roosevelt. "The ""Brownsville"" Raid, " first published in 1970, is John D. Weaver's searching study of the flimsy evidence presented in a 1909-1910 court of inquiry. That court had upheld the president's action and closed the case against the soldiers, not one of whom had ever been found guilty of wrongdoing. The case remained closed until 1971 when, after reading "The Brownsville Raid, " Congressman Augustus F. Hawkins of Los Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department rectify the injustice. Amid a flurry of national publicity, honorable discharges were finally granted in 1972. All were posthumous except for that of Private Dorsie Willis, who received his in a moving ceremony on his eighty-seventh birthday."

Hopping on the border; the life story of a bellboy.

by

Hopping on the border; the life story of a bellboy.

by

Users can further edit the search results by age range, collection type, educational feature, and more by clicking "Refine Search."

The Smithsonian Learning Lab is about discovery, creation, and sharing.

The Smithsonian Office of Educational Technology (OET) created the Smithsonian Learning Lab to inspire the discovery and creative use of its rich digital materials—millions of images, recordings, and texts. It is easy to find something of interest because search results display pictures rather than lists. Whether you've found what you were looking for or just discovered something new, it's easy to personalize it. Add your own notes and tags, incorporate discussion questions, and save and share. The Learning Lab makes it simple.

Appointments are recommended for most new researchers. Our team is available in Brownsville and Edinburg to assist you with identifying resources.