Our institution in the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas sits on the ancestral land of the Karankawa, Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan, Ndé Kónitsąąíí Gokíyaa (Lipan Apache), Carrizo/Comecrudo, and Rayados/Borrados. We acknowledge and pay respect to their Elders and their past, present, and future peoples, cultures, languages, and communities.

IMPORTANT: UTRGV Special Collections and Archives recognizes Native American Sovereignty and seeks to accurately and respectfully honor and represent indigenous people's heritage, history, and culture using their preferred terminology. Therefore, our staff welcomes suggestions for restorative efforts to improve description and representation. Please feel free to contact us if we can improve our cultural sensitivity for this research.

This research guide aims to help students interested on researching the Karankawa peoples of the Texas Gulf Coast. Resources held by UTRGV Special Collections and Archives in our physical and digital repositories are chiefly secondary sources, especially publications. Primary sources on the Karanakawa are not available via our institution but information has been provided for accessing external resources.

We strongly recommend visiting the website for Karankawas: People of the Gulf Coast and the Native Land App, which is intended to help map Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages.

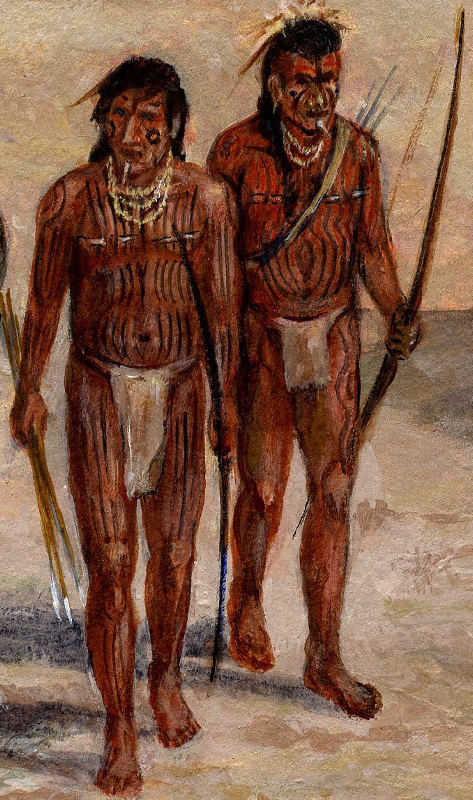

The often maligned indigenous peoples of Texas, falsely labeled as cannibals, the Karankawa people of the Gulf Coast of Texas are named for their common Karankawan language and shared culture. According to historians, the "name Karankawa has not been definitely established, although it is generally believed to mean 'dog-lovers' or 'dog-raisers'." They were described as tall people with mud painted and tattooed bodies, who carried long bows and fashioned projectile points from shells. Their seasonally nomadic bands traveled by dugout canoes, lived in wigwams, ate fish and shell fish, and drank tea brewed from yaupon. Early historical accounts also labeled them as Carancahuas, Coapites, Cocos, Cujanes, and Copanes. The Spanish deployed missions in South Texas in an effort to gain a permanent stronghold and subdue the native peoples through the process of "missionization" and cultural assimilation. However, following a series of conflicts with Texas settlers, the Karankawa were systematically exterminated between 1822 and 1852. By 1858, the Karankawa remaining in (driven south to) Mexico were annihilated.

Read more online via https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/karankawa-indians

Marker reads “In this area is one of several known Karankawa campsites or burial grounds. Now extinct, the nomadic Indians lived along the Texas coast, depending on the Gulf for survival. In 1528 they aided Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca, but resisted all intruders from the time of the French expedition of La Salle in 1685. The tribe later declined because of disease and warfare with pirates and Anglo-American settlers. Known for tall tribesmen and alleged practices of ceremonial cannibalism, they had virtually disappeared from Texas by the 1840’s. This campsite was discovered in 1962.”

:quality(75)/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/5d13b1524a73a19815ac5267308a8dc5/Indigenous%20People%20of%20the%20Coastal%20Bend%20Protest%20CS%20TT%2008.jpg)

The article offers information of Karankawa Indians of the Texas Gulf Coast region encountered approximately three hundred French invaders building an isolated fort. Topics discussed include Jean-Baptiste Talon, a ten-year-old and one of the six adoptees, lived with the Karankawas for around two and a half years; and his testimony of life among these coastal First Peoples is the most extensive first-hand account about these Native Americans.

Seiter focuses on the Karankawa-Spanish war from 1778-1789. For three days, cannons on Captain Luis Antonio Andry's vessel bellowed as a beacon for Gomez and the four other missing sailors. The men remained unresponsive. Two Karankawa brothers, however, appeared on the shore and approached the ship in a dug-out canoe. When Andry called out to the duo, one of the Indians answered back in fluent Castilian Spanish. He said that Don Luis Cazorla, the commander of La Bahfa, had tasked them with aiding any endangered vessels on the coast. A relieved Andry welcomed the pair aboard. Most Karankawas did not want war. Composed of multiple tribes, they were not a unified or singular entity. Each had different goals, each had their own motivations. In Joseph Maria's day, there existed five Karankawa-speaking groups that shared a similar culture: the Carancahuas, the Coapites, the Cocos, the Copanos, and the Cujanes.

A study of a letter from the Spanish governor of Texas, Domingo Cabello, written in San Antonio in spring 1779 is presented with emphasis on its significance. The letter which comes from the Bexar Archives reveals valuable information.

The Struggle for Texas, 1820-1879

A project of The University of Texas at Arlington Center for Greater Southwestern Studies and UTA Libraries that seeks to map sites of conflict between Native Americans and Euro-Americans in Texas from the creation of the First Mexican Republic to the outbreak of the U.S.-Mexico War (1821-1846)

HISTORY OF HUMAN ACTIVITY ON PADRE ISLAND

"Most of Padre Island has remained in its primitive state since humans first set foot on it. The natural resources of Padre Island and Laguna Madre have been used in simple ways by the three main groups who have visited and inhabited the island — Indians, Spaniards, and Americans. Small tribes of nomadic Indians hunted on the island and fished in Laguna Madre. Both Spaniards and Americans recognized the value of Padre as rangeland and took advantage of it. Now, with the establishment of Padre Island National Seashore and the preservation of a large part of Padre's environments, most of the island will be maintained in its primitive character..."

This website and blog provides insight into the appearance, diet, language, territory and much more about the Karankawa peoples of the Gulf Coast. The site also provides a chronology of archival documentation relating to the indigenous tribes with links to additional resources, including the Bexar Archives.

The Indigenous Cultures Institute was founded in 2006 by members of the Miakan/Garza Band, one of the over six-hundred bands that resided in Texas and northeastern Mexico when the Spaniards first arrived. The site provides access to a wealth of programs and resources, including Coahuiltecan language, Nakum Journal, sacred sites, performances, and more.

The Bexar Archives are described on the Briscoe Center for American History website as “the official Spanish documents that preserve the political, military, economic, and social life of the Spanish province of Texas and the Mexican state of Coahuila y Texas. Both in their volume and breadth of subject matter, the Bexar Archives are the single most important source for the history of Hispanic Texas up to 1836.” Included with these documents of the past of Spanish Texas are the interactions between the Spanish settlers and the indigenous peoples of Texas. These sources are useful for learning about how the Spaniards interacted with native peoples, what they thought about them, and overall how they treated them. The Bexar Archives digitized materials can be viewed translated or in their original form online or through the UTRGV Special Collections and Archives microfilm collection in Brownsville

There are 15 maps between 1700 and 1875 depicting the regions of the Karankawa peoples. Several of these maps are available to view online, including the manuscript (hand drawn) Mapa Geografico de la Provincia de Texas (1822), by Stephen Fuller Austin.

The research guides compiled by UTRGV staff and students are intended to assist patrons who are embarking upon new research endeavors. Our goal is to expand their knowledge of the types of resources available on a given topic, including books, archival materials, and websites. In so doing, our compilers have taken care to include collections, digital items, and resources that may be accessed not only through UTRGV but also via other institutions, repositories, and websites.

We wholeheartedly respect the research interests of others. Therefore, please contact us if you wish to submit a resource for consideration, or if you have a question about or an issue with a specific cited resource.

The Museum has also published a graphic novel called, PERSECUTION: KARANKAWAS, OUR LAND, which can be viewed online via https://www.dhhrm.org/graphic_novels/

Appointments are recommended for most new researchers. Our team is available in Brownsville and Edinburg to assist you with identifying resources.